The Hidden Value of Smart Contracts: Measurability

Most common flaws existing in natural language contracts are remnants of either older contracts that have since evolved or as contrary clauses in contracts that cover interrelated activities. When it comes to smart contracts, coding language requires events, rules and other business logic to be absolutely clear — and this requirement forces many companies to revisit their current contracts with fresh eyes for simplification and clarification.

Let’s say you buy a candy bar by dropping coins into a vending machine coin slot, selecting the candy, and voilà, your purchase appears. That’s how a smart contract works; consider a smart contract as really just lines of code or language that can capture physical events or services like dispensing a candy bar from a vending machine. It’s a series of if:then transactions: if is the payment and selection, then is the dispensing of the candy bar and return of any change if applicable.

Smart Contracts 101

Smart contracts produce touchless and seamless transactions. Where manual processes take days, weeks or even months to complete, smart contract technology can automate commercial transactions in real time. (See Blockgeeks’ article that expands on this with simplified detail.)1

An article by Ambisafe titled Smart Contracts: 10 Use Cases for Business reports that smart contracts are most often used (but are not limited to) banking, automatic payments, tax records, insurance, real estate, supply chains, internet of things (IoT), gaming and gambling, authorship, IP rights, life science, health care. Smart contracts “get rid of redundant actions and make them run automatically.”

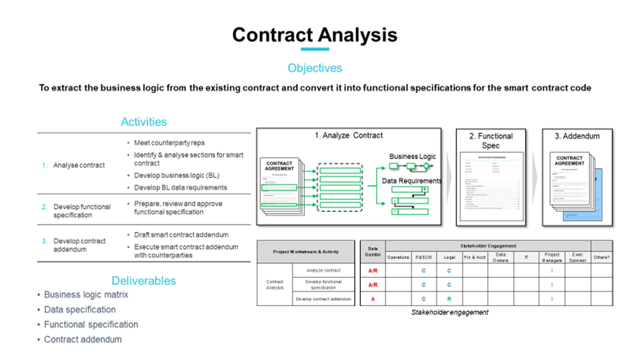

The segue from manual processes to smart contracts involves multiple steps. Since smart contracts are just an encoding (data encryption) of the business rules of any contract, as such, coding must be precise, defined and consistent. Contractual parties must collaborate to take the rules and intent of their natural language contracts and translate it into logical rules for coding.

The high standard of analytical discipline imposed by computer coding and testing can flag previously unknown contractual pitfalls for discussion including:

- contradicting clauses that can generate potential legal loopholes that open the door for disputes;

- vague expectations and lack of alignment between originators of a contract that lead to active blind spots and differing definitions of measurement terms;

- inefficiencies attributed to writing contracts without a digital perspective; and

- residual clauses left in a contract covering outlandish events.

The most effective smart contracts identify what really matters in service delivery and define that service in measurable terms. By contrast, when manually produced contracts are written in language that is open to interpretation and negotiation, service delivery slows down while processes are held up over invoicing reconciliations and disputes and, as a result, elongated payment time frames.

Smart contracts are measurable today

Sometimes companies already have contracts with measurable metrics, but the missing piece is a neutral check on the times and quantities. In a recent project with the Offshore Operators Oil & Gas Blockchain Consortium,3 smart contracts were deployed to automate invoice payments for water haulage.

The program revolved around barrels of saltwater produced by oil wells as a byproduct and their safe transportation and disposal. Since the pricing was mostly by the barrel, and the vendors submitted their claimed quantities tied to barrels, it was straightforward to identify all meters owned by the buyer or third parties that could check the quantities reported by the truckers. With two or three points of validation for volumes, counterparties in this smart contract were able to automate payments as long as the measurements matched within a certain tolerance — in this case of 1 to 2%.

Contracts with measurable potential

Most contracts have a mix of measurable and/or hard-to-measure services or goods within delivery that can add layers of incentives and modifiers to the process. For example, in an upstream drilling fluids delivery contract, a service provider rents an oil company volumes of oil-based mud in addition to other chemical components kept on consignment at the site. These additional materials are consumed and paid for as required to adjust mud chemistry and are in constant fluctuation.

Although digital methods exist to measure volumes of drilling fluids, measurements frequently captured in one project participants’ system rely on manual entry, an error-prone process. The result is plenty of mismatched numbers where each party believes in a different account of events.

However, if each party takes a step back to examine the requirements at hand, specifically the mud chemistry and the density at certain depths according to geologic formations and the well plan — then another, more efficient approach is available. Rather than relying on service personnel to manually type in consumption reports and then argue about disparities, the two sides could instead agree to use data from the drilling rig’s managed pressure drilling system and mud tanks to measure both the original volume of rented mud delivered and returned as well as the density of the mud at given depths in the hole.

The result could be a smart contract model where volume and density at depth are the metrics measured by a neutral third-party physics model with high quality meters as inputs. This approach allows for the costs of mud to be rolled into a single daily rental rate per cubic meter that can be calculated. It would produce final daily charges every 24 hours, providing both clarity and finality to counterparties up to 180 days faster than current contracting models.

Contracts may seem unmeasurable, but is that true?

Many contracts require expert judgment about the quality of a particular deliverable, such as a weld, a well log from a downhole tool or an engineering drawing package for a construction project. Smart contracts are not capable of providing a human quality check; however, companies should not let the requirement of one or two manual steps in an otherwise seamless process force 100% manual processes.

If parties use project management software that allows engineers to accept certain work packages, digital inputs can still trigger an automated smart contract process resulting in payments — perhaps with the record of who signed off on the drawings package and an encrypted copy of the drawings themselves as evidence. A shared, immutable record of the evolution of any particular work package from drawings to purchase order, delivery on site and eventual install by a foreman’s crew is conducive to value. Even though certain actions require manual work, progress and completion can be captured digitally via Radio Frequency Identification (RFID), visual scanning or other digital reporting data sources to trigger the automated execution of payments via smart contract technology.

Smart contracts produce clarity

Implementing smart contracts is a process that yields more clarity and transparency to benefit all involved parties, vastly improving time to invoice and time to pay.

As organizations shift their contracting mindset to adopt new models focused on neutral, clear metrics derived from data captured in the field, the complexity of hundreds of contract pages may be boiled down to a single page matrix. Performance and incentive-based contracts will become more feasible and desirable, running daily and providing near real-time spend and revenue visibility for buyers and sellers alike.

--

This article was authored by Andrew Bruce, Founder and CEO of Data Gumbo and was originally published at World Commerce & Contracting.